സംവാദം സമന്വയം സൗഹൃദം

ഒരു പെണ്ണിടം

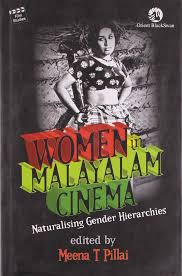

Malayalam Cinema: A Gendered Reading

Dr.Meena T Pillai

More than eight decades since its inception the language of Malayalam cinema has remained largely male dominated, displaying a curious apathy and a lack of sensitivity to the issues faced by the real women of this land. The much hyped Kerala Model of Development, inspite of its spectacular social development indicators which helped transport the image of Kerala to enviable heights, has not augured well for the women of this state in terms of a liberatorial potential that would translate into their everyday lives. These commendable indices like high levels of female literacy, employment, sex ratio and health achievements together with one third reservations of seats in local governance bodies are often believed to indicate that the women of Kerala have achieved a fair degree of social and political empowerment in the public domain. It has also contributed to the creation of ‘the myth of the empowered Malayali woman’ and its mystique. However none of these indices seem to find a positive echo in the images of women on the celluloid in Kerala. The tragic fate of P.K.Rosy, Malayalam Cinema’s first heroine, hounded both by caste and patriarchal forces, proves a case in point. Her social ostracism and brutalization illustrate that moral and sexual policing, both off screen and on it, have deeper roots in Kerala than what we would like to believe in. The unpardonable crime was not only that a Pulaya girl acted as an upper caste woman, but also that a woman could dare to inscribe herself so indelibly in so public a space as the movie screen. It does reveal the gender biases, sex role expectations and definitions of the ideal feminine prevalent in Kerala society at that time, and which has been a crucial marker of the discourse of our cinema from then on. From Vigatha Kumaran (1928) till date women on screen in Malayalam have joyfully surrendered their independence and identity, too willing to be putty in the hands of male desire and the male gaze. All through its eighty-five odd years of history Malayalam Cinema has, time and again, colluded with reformulated patriarchal ideologies to function as a false mirror, one which has the magical and delicious capacity to reflect the figure of the Malayali man twice or thrice its natural size while cutting down the figures of women to the tiniest possible proportions. Malayalam Cinema thus provides strong clues to the gender paradoxes that comprise the blindspots of Kerala’s experience of modernity. A cross historical analysis of movie images of women would reveal that it is through bargaining and compromising their autonomy and agency within the private sphere that the women of Kerala seem to have been able to negotiate their way into the public domain. These screen images bear testimony to the double burden and reiterative identification with familial norms and ideals which have helped fetch for the women of Kerala a visibility in the paid work force of the state. Here again, paradoxically enough their pay cheques enhance only family exchequers and hardly ever guarantee them either financial autonomy or individual mobility. That the liberal democratic spaces of Kerala’s public domain are increasingly becoming punitive and disciplinary as far as enforcing gender norms are concerned has been the cause of a rising anxiety amongst culture critics. The polyfocal terrains of the early movie hall have eventually been stamped as a masculine space. The tragic fate of Rosy and the first Malayalam movie signals the subsequent taming and grooming of all women in the public sphere in Kerala who would dare to offer themselves to the specular Malayali male gaze. It is only by the fifties that Malayalam Cinema breaks free from Tamil influences and begins to consciously evolve an idiom of its own. However its egalitarian, socialist base, derived from progressive reformist literary traditions that time and again invokes the language of social realism only seems to neutralise caste while strengthening gender stereotypes. The much celebrated Neelakuyil (1954) being a case in point. Malayalam Cinema during this period, in negotiating the transition of a traditional society to more modern, secular registers, effects this task through imagining the modern bourgeois family and reallocating new roles and models, especially for women to emulate within the confines of this paradigm. The woman is thus further tamed and made docile under the sign of this conjugal ideal and the process of regulating female sexuality. This project of sabotaging women – through love, continues into the sixties. It is through copious tears, self sacrificing acts of martyrdom and torture, self effacing acts of compassion and tenderness that Malayalam Cinema offers to legitimize its women and procure for them some amount of respectability. The New Wave, in the seventies, with a host of brilliant directors like Adoor Gopalakrishnan, G.Aravindan and T.V.Chandran among numerous others, followed by advocates of a Middle Cinema like K.G.George and Padmarajan did make concerted attempts to critique the tokenization of women and the idealization of the hegemonic male subject in the backdrop of the seismic social and economic transformations of Malayali society. The high modernist imperatives of the New Wave could have unwittingly contributed to the dichotomization of movies into art and popular, where the transitive political language of the former failed to capture the imagination of the masses while the melodramatic conservative language of the latter carved the popular imaginary. One also has a nagging suspicion that women themselves remained on the margins of such viewing experiences and the much lauded film society movement failed to accommodate the feminine or offer less gendered public spaces for the female spectator. By the eighties and nineties the rhetoric of the popular in an overtly commercial cinema was successful in hitching female fantasies of empowerment and transformation on to the pleasures of consumerism and the allure of commodity signalling the final blow to the emancipatory possibilities that cinema could hold for women. The collusive tactics of capitalism, neo-conservatism and patriarchy together contribute to a refeudalization of public sphere as many cinemas (Aaram Thampuran, Ravanaprabhu, Narasimham, King, Commissioner) post nineties, illustrate. Of late a new crop of movies (22 Female Kottayam, Salt and Pepper, Chappa Kurissu, Trivandrum Lodge) flaunting the nomenclature ‘New Generation’ seems hugely successful in subverting some of the entrenched paradigms of Malayalam Cinema and reviving an industry that was in the grip of a nameless apathy. While seemingly accommodative of the anxieties of a generation which has been moulded by the exigencies of liberalization as also the iconographies offered by the satellite television boom, and exposure to the new cultures of digital and virtual worlds, this kind of cinema still remains by and large politically and morally ambivalent. While posing as radical chic and wallowing in a public self-stylization, whether this cinema can offer the celluloid paper dolls of Kerala a political identity other than their familial or sexual connections to men seems largely debatable. It is time Malayali women realized that the problems they confront in real life are ideologically entangled with those of the imagined and idealized women on screen. So instead of being passive consumers they should learn to read these images politically and seek to understand the processes by which they are naturalized.

പിന്നോട്ട്

സ്ത്രീകള്ക്കുള്ള അഭയകേന്ദ്രം.

മാനസികരോഗികള്ക്കും മദ്യപാനികള്ക്കും ചികിത്സ.

അത്താണി, അഭയബാല, ശ്രദ്ധാഭവനം,

http://www.abhaya.org/

ശ്രദ്ധിക്കേണ്ട വെബ്സൈറ്റുകളും ബ്ളോഗുകളും

http://www.menstrupedia.com/

www.sakhikerala.org

http://www.anveshi.org.in/

http://www.sewakerala.org/

http://keralawomenscommission.gov.in/vanithaweb/en/

http://www.abhaya.org/

http://www.kswdc.org/

http://www.unwomen.org/en

http://ncw.nic.in/

http://www.hrln.org/hrln/kerala.html

http://www.devakiwarrier.org/

http://aidwaonline.org/map/kerala

http://keralasamakhya.org/

http://www.nwmindia.org/

http://womenwritersofkerala.com

.jpg)

.jpg)